Fortune 500 CEOs Fail This Simple Test On Decision-Making. Will You?

Plus: Get a free new book I've been excited about!

You’re Probably Making This Thinking Error Right Now (And It’s Costing You):

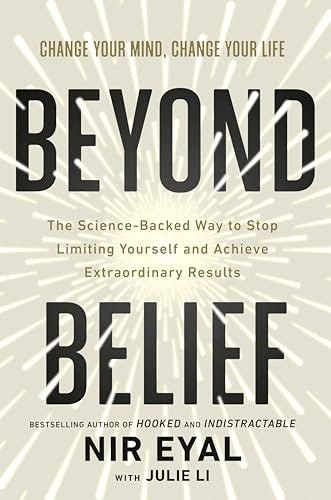

Take a look at the following picture of “Snuffalufagus”—the woolly character from the kids show Sesame Street. Tell me what you observe about this scene:

I have a confession. You’re the millionth person I’ve shown this photo to. For about a year, I’ve been putting this up on the big screen at conferences and leadership workshops, and quizzing audiences about it. (Sesame Street quizzes are a dicey move to give to Fortune 500 CEOs, I know, but bear with me!)

Very often, when I ask “What do you observe about this scene?” the first commenter in an audience will say something like,

“Snuffalufagus is about to eat a giant spaghetti with meatballs.”

Other common answers:

“Suffalufagus is hungry,”

or

“Snuffalufagus likes spaghetti.”

Now here’s the point—both of the audience exercise and of this post:

Each of those answers reveal a common mistake in the way human beings naturally approach decision-making.

It’s a mistake that affects companies every day, in every department.

It’s a mistake that affects the tiny decisions in your life just as much as the big ones.

And it’s a mistake that once you start noticing it, you’ll see it everywhere.

Separating Observations From Stories

Did you notice the wording I used to frame the Sesame Street question? I deliberately chose the word “observe”—as in what do you observe about the photo?

Talking about Snuffy being hungry, or liking spaghetti isn’t an observation. It’s a conclusion. It’s a story that you’re telling yourself, based on what you observe.

Saying that Snuffy is about to eat the spaghetti isn’t an observation, either. It’s a prediction. It’s telling the future.

An observation, in this case, is much more boring.

Snuffalufagus is standing in front of a plate of spaghetti. He’s wearing sunglasses. He’s by himself. The spaghetti has a single meatball.

We don’t actually know if he’s going to eat it. We don’t know if he loves it. We don’t know if he’s hungry. We just know what we observe: he is there, and so is the spaghetti.

From a psychology standpoint, the boringness of these observations is part of the problem. Our brains work so quickly, and want to draw meaning from what we observe. So we skip straight from what we observe to what we think without realizing it.

Now, around this time, I usually ask a second question: “What’s an alternative story you could tell about this scene, based on the observation that Snuffy is standing there wearing sunglasses, and that there is spaghetti in front of him?”

One story could be that Snuffy just had laser eye surgery, and he can’t even see the spaghetti. Based on the photo alone, that story is just as likely to be true as the story that Snuffy is about to eat the spaghetti.

Of course, with more information, we might be able to predict which of these stories is more likely (say, if you have seen a lot of Sesame Street and know the character). But we would be making a mistake to definitively conclude either story without more information.

Putting Our “Stories” In Terms Of Science

Over the centuries, scientists have developed an effective method for avoiding jumping to conclusions. As a refresher, it goes like this:

Make Observations

Ask Questions (based on those observations)

Form Hypotheses (based on the first two steps)

Run Tests (to disprove the hypotheses, til you end up with something you can’t disprove)

Most of us aren’t scientists. But our brains instinctively run through a crude version of the scientific method all the time.

The thing is, because our brains are fast and take shortcuts, we naturally skip from Observation to Hypothesis. We observe something, then we make up a STORY in our heads about it.

And then we convince ourselves that our story—the hypothesis we instantly make up to make sense of things—is an observation. We see Snuffy and the plate of spaghetti and skip to “he’s going to eat it.”

I have observed hundreds of Fortune 500 executives confuse their hypotheses with observations over the last year—starting with the Snuffalufagus Test, and escalating to more serious business scenarios. Smart and successful people are especially good at convincing themselves that their story is the same as an observation.

Speaking of convincing ourselves…

A quick break for an exciting offer for my readers!

Win a Copy of Beyond Belief by Nir Eyal:

Why do you give up on goals even when you know what to do? Nir Eyal (author of Hooked and Indistractable) spent 5 years answering that question. His new book Beyond Belief reveals that the #1 reason people fail isn’t lack of strategy or discipline. It’s that they quit too soon. The book teaches you a science-backed way to leverage your beliefs to persist when most people give up.

I read an early copy and absolutely LOVED it. It completely rewired how I think about performance, pain, and perception. In fact, I like the book so much that I’m sponsoring 30 copies to give to you all. To stand a chance to win:

(Available to US residents only for the moment. Deadline 13 December 2025)

Humans make the Snuffalufagus mistake all the time. Especially at work.

I once had a colleague who noticed that the direct deposit for his paycheck didn’t come on the usual day of the week. He sent an email to a handful of company executives saying that he wasn’t aware that we were firing him, that he was upset to find out this way, and shame on us.

It turned out that our payroll company was processing everyone’s direct deposit later than usual because of a US bank holiday… a holiday that they don’t have in the country this worker was from.

No one could blame him for not knowing this. Unfortunately, he skipped from his Observation (no paycheck on the usual day) to his Hypothesis (we were passive-aggressively firing him) and sent a mass email that embarrassed him. Sadly, the way he handled this decreased the whole leadership team’s trust in him.

Had the employee taken the Snuffalufagus Test before, he might have noticed the late paycheck, felt a jolt of anxiety, and then said to himself, “But before I make a decision on what to do, what are the Observations here?”

The core, unembellished observations would be that (a) paychecks historically deposited on Monday, and (b) no paycheck had been deposited on Monday.

Given those observations, several possible stories could be true.

Articulating our observations helps our brains to create space to process logic. E.g. “there was no deposit on the usual day” does not itself mean “you’re fired.” By the same leap in logic, one could as easily conclude “instead of direct deposit, everyone now gets paid in suitcases of cash at the end of the week.”

(Which is how I want to get paid from now on.)

Snuffalufagus Test failures sometimes don’t matter much. Who cares what’s going on in the spaghetti photo? But when we have impactful decisions to make—say, when something has gone differently than expected—failure to separate observations from Hypotheses leads us to confuse made-up stories with reality. And once we have a story in our head,it is often hard to shake it, good or bad.

Overreactions to leaps in logic can range from embarrassing to catastrophic, but a simple habit can help us prevent them:

Whenever something goes differently than you expected, step back and ask yourself, “What do you observe?”

Then separate that out from, “What do you believe?”, “What do you think?”, or “What do you conclude?”

Then, instead of making accusations or, ask neutral questions based on the observation (“I observed X. What does that mean?”).

I’d dare say that Snuffalufagus—who if you know a thing about him, it’s that he tends to take curveballs in life slow and steady—would approve.

Make a great day!

—Shane

An award-winning business journalist and Tony-winning producer, Shane Snow is a bestselling author and renowned speaker on leadership, innovative thinking, and storytelling.

One way to counter this I have found is to count to 4 before I make a decision. It gives my brain a chance to engage directly with the image.

I also find it helpful to double-check my observations and sometimes supplement them with external fact checking. To wit:

1) This character's name is “Snuffleupagus,” not “Snuffalufagus”.

2) In the picture currently showing on this post, he does not appear to be wearing any sunglasses. He *does* have notably long and thick eyelashes, as usual.