Death and Storytelling

Feliz Dia de Muertos: An essay on the stories that make us care as human beings.

It was shortly before my 30th birthday when I learned how I was going to die.

This is my favorite opening sentence of anything I’ve ever written.

Grammatically, it’s not exactly a masterpiece. Creatively… well it starts with “it was”... which is maybe the most cliché way to begin.

But I love that line. And so did a half-dozen book editors who competed with their company wallets after reading it.

This is the sentence at the start of the proposal that got me my biggest book deal.

Why does such a grammatically-uninspiring first line work so well? It’s because of what two-time Pulitzer prize winning journalist Gene Weingarten says:

“A feature story will never be better than pedestrian unless it can use the subject at hand to address a more universal truth. And, as it happens, big truths usually contain somewhere within them the specter of death.”

Today, I’m writing from my kitchen table, in view of my family’s “ofrenda” for Dia de Muertos. It’s a tribute to our loved ones who have died. Every year we put it up, to remember them. Two years ago, we added my grandfather’s photo to the ofrenda. This year, Grandad was joined by a family member who we lost to suicide.

I’ve written a lot of stories, and I’ve written a lot about stories. And I’m not what someone would describe as “a gothic person,” but if you were to catalogue the opening stories in my body of work, you would discover not only that I’ve got an 8th grade vocabulary, but also that I spend a disproportionate amount of time raising “the specter of death” and loss.

Case in point, here’s how I begin 4 of the 8 chapters of my book Dream Teams:

“The Chicago detectives were in Baltimore, of all places, investigating a train robbery (of all things!) when they learned about the plot to kill their hometown congressman.”

“General Andrew Jackson was fresh off his latest massacre when he received the order to lead an army of pirates, whores, Choctaws, and black guys to save America from destruction.”

“Four-year-old Malcolm Little’s earliest memory was of white supremacists burning down his house.”

“Fumiko Nakamura and her husband Takekuma would have never guessed, at the time they were thrust out of their Los Angeles home at gunpoint, that their son George would someday be a massive celebrity.”

It gets worse! In my Dream Teams stump speech, I usually start with a story about thinking I was going to die in an old van when I was a kid.

In my Thinking Ahead speech about adapting in a world of AI, I usually start with the story of contest that caused a deadly famine.

In my Smartcuts speeches about lateral thinking, I often start with a puzzle about being burnt to death by a dragon, or a parable about an old lady who might die in a storm.

Why do I do this?

Because like all storytellers, I want people to care about what I have to say.

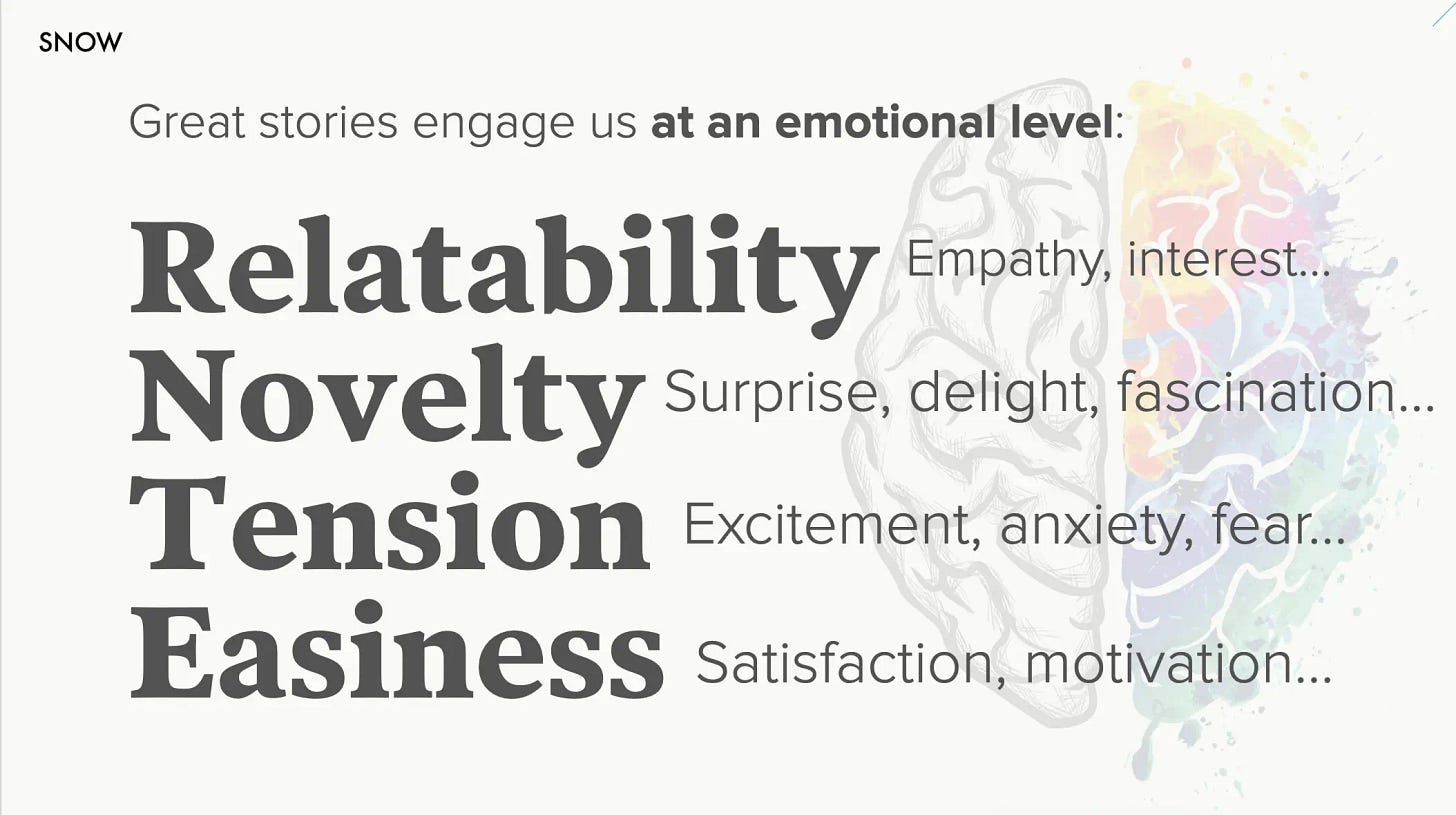

A few years ago, in The Storytelling Edge, Joe Lazer and I made a scientific case for four elements that make the difference between good stories and great stories—whether you’re a business trying to build relationships, a writer trying to build an audience, or simply a human being trying to connect.

The elements are: Relatability, Novelty, Tension, and Ease of Understanding.

And if you think about it, Death does it all. It’s universally relatable; all of us face it. It’s inherently novel; we don’t know when or how it will come. It’s obviously full of tension. And it’s easy for us to understand the stakes of a story when Death rears near.

The best storytellers understand this. (I’m not calling myself one of them. I’m saying I think about death as a writer on purpose, because I know it’s important and it works.) Death doesn’t always have to be on the nose to be lurking in a story. It just has to be there when the audience asks, “Why does this matter?” to say “Because at the end of the day life matters.”

The point for you, as a human being who tells stories every day—whether out of your human nature or deliberately in your work—is that during this Halloween-y, Day of the Dead-y time of year when we tend to think about death more than usual, remember that your fellow human beings care much more about stories that mean something than they do about grammatically-excellent opening lines or run-on sentences like this one.

Because as Kafka said, “The meaning of life is that it ends.”

An award-winning business journalist and Tony-winning producer, Shane Snow is the bestselling author of Dream Teams and a renowned keynote speaker on leadership, innovative thinking, and storytelling.